Carolyn Kagan

Inaugural professorial lecture - Manchester Metropolitan University, Jan 30th 2002

Introduction

It is a pleasure to have the opportunity to talk to you tonight and I thank you most warmly for coming. In one way or another most people here have contributed to the way I work and to my understanding of the possibilities for a community psychology. For some, this has been as family and friends; for some, it has been as colleagues, mentors or supervisors; for some, it has been as participants in, and contributors to action based research and development projects; for some, it has been as students. This observation, in itself, presents a challenge to the discipline of psychology. Western social psychology views people very much as individuals, separate from others, responsible for our own successes and failures, our own health and well being, - albeit in interaction with others. When I think about the importance you have all been to me in the work that I do, I think about myself and my work more in line with the African concept, expressed through several Bantu languages (e.g. Zulu, Xhosa and Ndebele) of ubuntu.

Ubuntu:

Motho ke motho ba batho ba bangwe/

umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu

A person can only be a person through others.

Translated literally, this means a person can only be a person through others. It is through you that I am who I am, and do what I do - for which I thank you.

The title of the talk is taken from a 'conversational book', We make the way by walking in which Myles Horton and Paulo Freire discuss their lifelong commitments to transformative radical adult education. It is also adapted from a poem by the Spanish romantic poet, Antonio Machado.

His poem describes the ethereal nature of the paths we walk through

life: how the way is not always clear and how, when we turn to look from

whence we have come, our footsteps, and the paths we have walked have disappeared.

Caminante, son tus huellas...

Caminante, son tus huellas

el camino, y nada mas

caminante, no hay camino

se hace camino al andar.

Al andar se hace camino,

y al volver la vista atras

se ve la senda que nunca

se ha de volver a pisar.

Caminante, no hay camino

sino estelas en la mar.

is your footsteps, there is no other.

Wayfarer, there is no way,

you make the way by walking.

As you go, you make the way

And stopping to look behind,

You see the path that your feet

will never travel again.

Wayfarer, there is no way -

Only foam trails to the sea.

Trnsl. A. Trueblood, 1982

Working, as I do, at the margins, out of the mainstream of psychology is a little like the journey of Machado's traveller. In this talk I am going to sketch some of the paths I have walked, sometimes in others' tracks, sometimes reluctantly, and sometimes forging a precarious way alongside only a few.

Some of these paths are now well trodden. Others have been diverted, and some seem to have disappeared, coming to nothing, but perhaps to re-emerge in the future.

Along the way, I have encountered a psychology that is confined by its purpose, methods and its discipline boundaries. It is by and large an unimaginative and sterile discipline and profession, invisible to many and of limited relevance to those people around the world, who are marginalised by the social systems in which they live. This resident, from a peripheral estate on which I worked, may just as well have been talking of psychology when she wrote:

(Angry resident from a Manchester over-spill estate to a local paper, April, 1998)

To date, community psychology, although well established in most other

parts of the world, is new to the UK. In this talk I am going to draw on

my own journeys through different kinds of psychological work to highlight

some of the limitations of British Psychology and map out some of the possibilities

for a community social psychology.

The rocky road of social psychology

When I began working in psychology, in the early 1970's my area of social psychology was a well trodden road, but was in crisis (that's official - there have been books entitled 'The crisis in social psychology', so it must be true).

by I.A. Parker

subjectivity and cognitive representations in people's social worlds. I walked along this road awhile, in the company of others who sought to change the philosophical base of psychology. The terrain we traversed was tricky and hard to negotiate. Probably because of this, remnants of this journey still characterise my work, and I remain committed to a more critical understanding of the meaning of peoples'lived experience.

This road is one that is now

well travelled: the social psychological M6 - no M60, a ring road, that

never quite gets to the heart of things that matter to people, goes round

and round in terms of understanding, but fails to branch out and create

any change. It is a road that has generated volumes of traffic, particularly

amongst academic, but also some professional psychologists,

This road is one that is now

well travelled: the social psychological M6 - no M60, a ring road, that

never quite gets to the heart of things that matter to people, goes round

and round in terms of understanding, but fails to branch out and create

any change. It is a road that has generated volumes of traffic, particularly

amongst academic, but also some professional psychologists,

but is inaccessible to the majority of people (not least because the

travellers have developed the equivalent of a CB radio language that is

dense, obscure and alienating). A liberated psychology should, I suggest

be transparent, comprehensible and available to all.

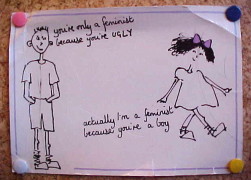

The ambush-track of feminist psychology

The 1970's and 80's were the hey days of the second wave women's liberation movement and the start of a critical exploration of psychology's irrelevance to women and the systematic gender bias within the discipline.

In 1980, I was the only woman in the psychology department of an Australian university. By request I gave what turned out to be a crowded public lecture, on the Psychology of Women. Thereafter followed a journey, accompanied by colleagues here to establish Psychology of Women as a part of the curriculum for the first time in the UK. There were attacks around every corner, to cries of 'bias', 'political', 'feminist' (at that time meant as a criticism) and it took several years to get the subject established in our degree programme.

Luckily for psychology and for both women and men, lots of other footpaths along the same barren moor were being forged at the time: they combined and the path is now a trunk road. Psychology of Women is now a division of the BPS, there are British based journals and feminist perspectives permeate (if they are allowed to) every branch of the discipline, both in terms of academia and professional practice.

I still know every twist and turn of this road, and feminist perspectives, as well as a concern with other forms of oppression, including class, race, ethnicity, culture, age and disability feature in all of my work.

A liberated psychology must, I suggest, deal with diversity, power, powerlessness and oppression.

The pack road along which people travel with heavy burdens, often ill-equipped, and with few places to rest along the way

This is a road I have found myself on repeatedly. On an early journey, I worked in what was then called a Senior Girls' Approved School. I met teenage girls, deprived of their liberty by the workings of a criminal justice system in which they were imprisoned for being outside the care and control of their parents or being in 'moral danger'. Many had been in care, part of a system that exposed them to further trauma and abuse, failed to keep them psychologically safe and abandoned them at (what was then) 16.

Nobody

So far so good I have been told

But how do I know it's going to hold?

I cant go on being some other than me

Oh - please help, it just can't be.

I've waited on my mum for ever so long

But I know she don't care

I've done so many things wrong.

I've been in and out,

I've been here and there

All in the short space of a year.

Will I go on or will I stop?

I really don't know.

What do I live for here?

It's getting to the stage

I just don't care.

Along this road, before I ever studied psychology, I began to understand a number of things about social behaviour and experience, as recorded in my diary at the time (June 1970):

Show me the prison, show me the jail

Show me the prisoner whose face has gone pale.

And I'll show you a young man with so many reasons why

And there but for fortune go you and I.

Psychology

Biological Bases of Behaviour

Development

Perception and attention

Learning and memory

Thinking and Language

Motivation and emotion

Personality

Social behaviour

A psychology, it was, that studied memory, learning, social relationships,

behaviour and so on as if they could be separated from the whole. I saw

little in this that would have helped the troubled girls I had worked with,

and little in the way of connections with what was clearly needed in terms

of social change. To this day, few psychologists travel this road supporting

people in their struggles to liberate themselves from an oppressive social

system. Those that do, not in Britain, but in, for example parts of Latin

America and Africa, are inspirational.

A liberated psychology must, I suggest, be capable of understanding experience-in-context; identifying oppression; identifying, challenging and resolving institutional abuse. It must also establish the ethics of commitment and care at its heart.

A little later on I travelled a similar road - one of Social Skills Training, , when I worked with people who were isolated, with few friends - called at the time, by psychologists, 'socially inadequate'. What an added burden such labels become! They reveal hostile social attitudes and, when coupled with prejudice and discrimination, a lack of tolerance and acceptance of diversity.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

In a world where responsibility for social isolation is laid firmly on the shoulders of the shunned and the isolated, psychologists (including me) contributed to this individualistic emphasis, through training and therapeutic interventions. And yet, quite clearly, the problems did not so much lie within the people themselves, but rather in the context of their lives, whether this be the other people around them, the opportunities to take up new roles, the policies and practices of professionals, or even the actual situations in which they found themselves.

For my part, this journey confirmed to me the damage done to people by the workings of a competitive, individualistic society, where perfection is expected and, by implication, those who are not perfect are seen as lesser and excluded. I know of some of the difficulties of repairing a fractured social identity, as I amongst so many other failed the 11 plus. Joan Plowright in her recent autobiography points to the long term social consequences of the 11+:

Fractured identities and societal responses need to be understood and policies and practices that contribute to the damage done need to be challenged. In the past, it was considered 'political' to, for example, challenge the prevailing educational hegemony; challenge Government policies of dispersing or corralling refugees and asylum seekers; challenge Governments that go to war for their own (and by implication our own) political purposes. If it is 'political', it is outside the realm of a respected scientific discipline - like psychology.

A liberated psychology must, I suggest, be able to work within this political arena and use its techniques and methods to expose ways in which societal policies and practices contribute to the fracturing of identity, and how prejudice, discrimination and conflict can be overcome by peaceful and non-violent means.

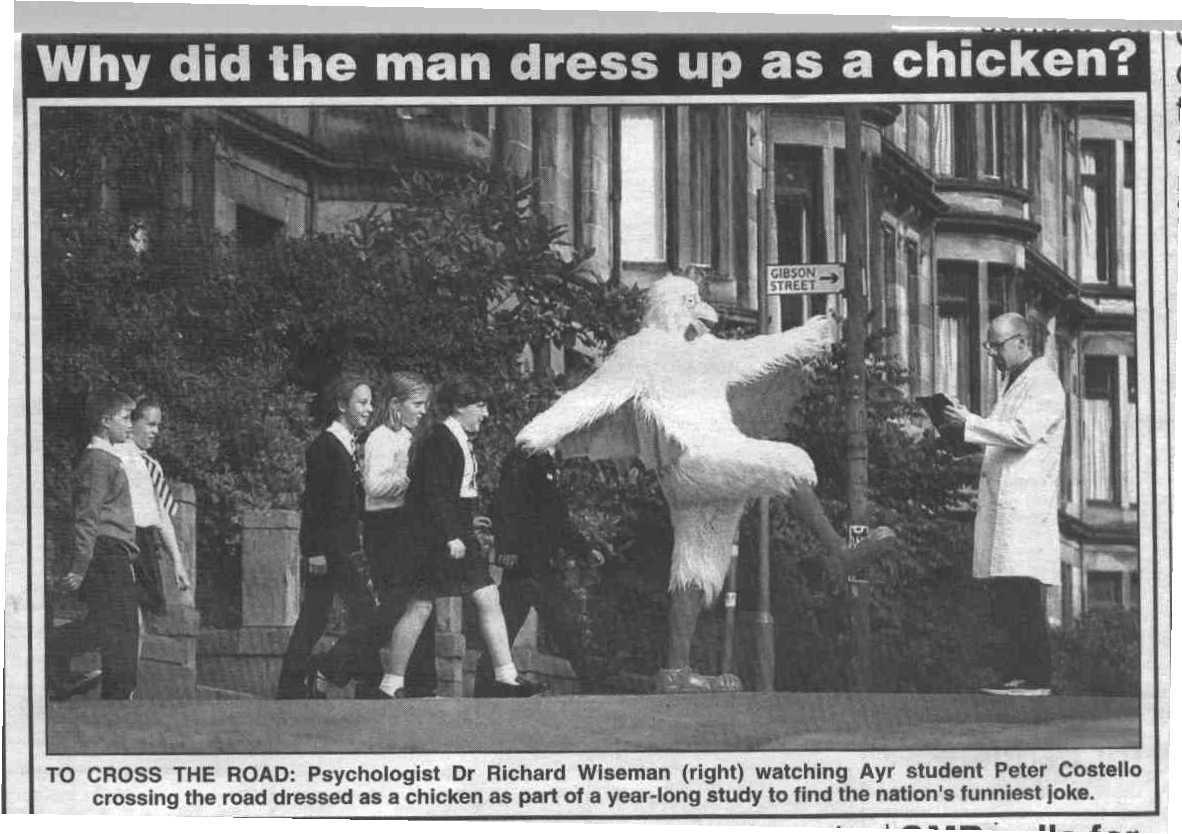

I have always argued that psychology could and should have something to say about and not be neutral about the need for change. Of course such challenges need to be rigorous, but the time has come to weaken dogged adherence to a positivist science - especially as these scientific investigations in psychology , that are held with such esteem, have resorted to timing human chickens crossing roads in order to reveal the country's favourite joke! (The picture was published in a national newspaper in 2001.)

Morning

Star

Morning

Star

Stumbling along unfenced roads with poor visibility

Walking a different pack road, I encountered another group of people. People living in poverty were virtually invisible within psychology. (People who lived often in appalling physical circumstances; sometimes with no work and with few local facilities; often getting by for years in and out of violent relationships; perhaps living with the long term effects of childhood trauma, but not knowing if or how it is possible to seek help; sometimes with addictions of one sort or another; raising children; being funny and warm; observing strong moral codes; loving and supporting family and friends.) People, whose way of life and whose livelihood have been shattered by social changes over which they have little control, and by successive local, National and international political and economic movements.

What social psychology has to tell us about interpersonal relationships, attitudes, group behaviour, social cognition and so on did not apply to their lives. Why should it, given that people living in poverty had rarely been part of the development of psychological knowledge (or indeed any other knowledge)? This point was brought home forecfully in the recent Independent Commission on Poverty, Participation and Power. As one local group of poor people said:

Geogdivide quote

Regrettably, Psychology has learnt little about ways in which poor people (in the UK or elsewhere) cope, survive and maintain their individual and collective integrity through group and community based action.. It has learnt little, too from links with other disciplines (such as community and social development), that may be able to share vital insights into the organisation of social life, as well as participative ways of identifying the need for and achieving change in areas of multiple deprivation. Psychology can tell us little about the mechanisms through which social change, alienation and exclusion from mainstream social life translates into altered family dynamics, and changed patterns of social behaviour at individual or group levels. It can tell us little about any generational differences in feelings of identity and purpose.

It will only be by walking alongside people, over long periods of time, listening, laughing, sharing anger and frustrations, that we might acquire some ways of understanding how theses loads are carried, what kinds of strengths people bring to bear, and may even lead to finding ways of helping people identify ways of lessening the loads. Long-time community psychologists from the USA, put it like this:

Travelling these pack roads

has clarified for me how aspects of the social system, as well as historical

changes in social relationships, can violate the psychological integrity

of people who are socially marginalised. Although psychology is concerned

with human behaviour and experience, it is invisible to the poor and dispossessed;

and the poor and dispossessed are invisible to psychology. The scope for

psychology to move beyond research and individually based interventions,

to become involved in, for example, social action, social impact analysis,

policy analysis and policy development at international, national and local

levels is enormous. But this must be in partnership with people most harmfully

affected by the policies and practices imposed upon them, and it must be

in ways that help people make connections with others, locally, nationally

and internationally.

Travelling these pack roads

has clarified for me how aspects of the social system, as well as historical

changes in social relationships, can violate the psychological integrity

of people who are socially marginalised. Although psychology is concerned

with human behaviour and experience, it is invisible to the poor and dispossessed;

and the poor and dispossessed are invisible to psychology. The scope for

psychology to move beyond research and individually based interventions,

to become involved in, for example, social action, social impact analysis,

policy analysis and policy development at international, national and local

levels is enormous. But this must be in partnership with people most harmfully

affected by the policies and practices imposed upon them, and it must be

in ways that help people make connections with others, locally, nationally

and internationally.

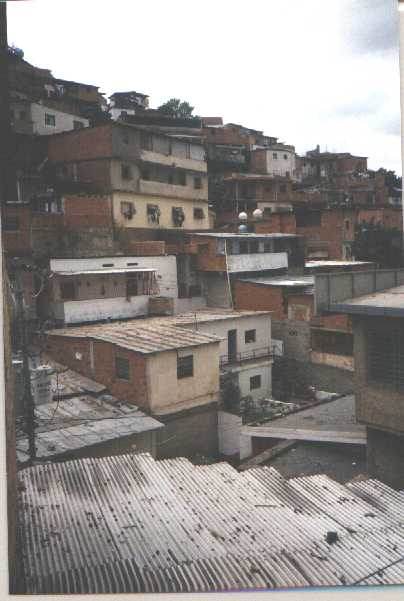

South African school; Venezuelan painting

I have met few psychologists on these pack roads - perhaps one or two

crossing over. As they pass through, their tracks disappear, leaving the

burdened travellers to struggle on. Our own international journal, Community,

Work and Family opens the way for sharing interdisciplinary work which

considers the impact of the major institutions of Community, Work and Family

on peoples' lives. The three domains cannot and should not be separated.

The burdens people are carrying are not theirs and theirs alone: they are social burdens that need to be addressed at a social level, preferably not through treatment, but more by prevention, collective self-help, social policy analysis and social action.

A liberated psychology must, I suggest, not only move beyond an individual

focus, it must move towards looking at social change and social action.

Further, it must contribute to social action as a vehicle for empowerment.

It must seek to understand and promote the interconnections between different

life spheres, and between people in different places and different socio-political

contexts. A liberated academic psychology must position itself in solidarity

with those who are marginalised and have hitherto been without a voice

in the discipline, or indeed in society.

The toll road that excludes and silences people

Since the early 1980's I

have worked with disabled people - mostly people with learning difficulties

- their families and the services that support them. It was along this

road that I discovered travellers (amongst whom were very few, but significant

psychologists) who were explicit about the value base of their work. I

participated in interdisciplinary work, across the north west region. Together

we worked towards a vision of a better society, - a future that coincided

with the dreams and aspirations of disabled people themselves. It was possible

to identify the barriers that excluded people from going forward, and sometimes

even to facilitate ways in reducing or eliminating those obstacles. In

the North West 2000 people no longer live in large scale institutions away

from the rest of us. Major other changes have been made to people's lives.

Since the early 1980's I

have worked with disabled people - mostly people with learning difficulties

- their families and the services that support them. It was along this

road that I discovered travellers (amongst whom were very few, but significant

psychologists) who were explicit about the value base of their work. I

participated in interdisciplinary work, across the north west region. Together

we worked towards a vision of a better society, - a future that coincided

with the dreams and aspirations of disabled people themselves. It was possible

to identify the barriers that excluded people from going forward, and sometimes

even to facilitate ways in reducing or eliminating those obstacles. In

the North West 2000 people no longer live in large scale institutions away

from the rest of us. Major other changes have been made to people's lives.

Most importantly, over the last 15 years, the disabled people's movement has grown and ways of enabling people themselves to have a direct influence over decisions about their lives have been found. However, far too many people with learning difficulties still live with relatively few friends, hemmed in by the services that are there to support them in leading fulfilling lives, and all too often abused by the very same carers. Families with disabled members still muddle along within an antiquated benefits system and amongst other people's negative attitudes. They often find it difficult to get information and the lack of co-ordination between services and workplaces means that they frequently cannot work and are confined to poverty.

Psychological practitioners, are increasingly walking this road, pushing for excluding barriers to be removed. Even so, it is too often the professionals who think they know best: it will only be by finding more, creative ways of involving disabled people themselves in identifying and overcoming the barriers to inclusion, that real progress will be made.

A liberated psychology must, I would suggest, be able to identify and help people dismantle disabling barriers to inclusion in a full social life.

Academic psychology, however, tires more easily and has not shown the same determination to overcome the obstacles to progress. The recent draft benchmarking statement for psychology (outlining the knowledge and skills required through an education in psychology) makes no mention of the role of policy analysis and the impact of health, education, and other social policies on people's lives. It includes no opportunities to explore the nature of large scale, inter-organisational change (not just understanding it, but carrying it out too). Mention of the skills of collaborative and co-operative work are sparse and the emphasis throughout is on individual not co-operative work and achievement.

In the research arena, priority is given (formally via the Research

Assessment Exercise) to publishing ideas, experiences and research in erudite

academic journals, which few practitioners, and even fewer family members

and disabled people will ever get to read. It is not enough to be silently

complicit in the workings of the academy - constant vigilance and challenge

is required, as well as resistance to the academic orthodoxy.

A liberated psychology would, I suggest, be one in which psychologists

work collaboratively and participatively with local people and with their

students. It is one in which psychological information and insights are

made available to all.

Not only must we find participatory ways of practising and researching, we must find ways of validating and reporting the lived experiences of our students and move away from the empty vessels-needing to -be- filled- with-knowledge (what Freire calls the 'banking' model of learning), to a more active one.

Rap picture

This track is being turned into a clear path, still with many obstacles, and tolls to be paid. However, slowly, some ways are being found of getting through.

By travelling the roads of the past, it has been possible to get a sense of direction for the future.

What are the possibilities for a community social psychology?

A number of possibilities for a different way of working as a psychologist have been revealed by walking these roads:

As community psychologists, then we would explicitly

The

rough and slippery track of community (social) psychology

The

rough and slippery track of community (social) psychology

Here, at MMU, we have been developing community social psychology as a way of combining some of the lessons learnt from previous journeys. There is little history of community psychology in the UK, and what there is, is largely 'traditional' psychology transported to community settings. So we have uncharted terrain to navigate, but we carry with us a store of learning that has come from our previous travels, and are aided by those in other countries and from other disciplines who have already begun to make tracks. Thus the way will be made by walking. It is likely to be a lonely road for us psychologists, but we will be joined by people, hitherto excluded from involvement, who will sustain us with their courage, fortitude and spirit.

As with all social innovations our course is set by a vision of what could be. In this post-modern, neo-liberal Western world in which we live, where every aspect of human experience has been commodified, I make no apology for resuscitating an emancipatory utopian dimension to psychological practice. I am convinced, along with others that it is only when we project our future in the light of what is, what has been, and what could be, that we can engage in the creative practices that will produce a better world for us all. It is the utopian dream of a better life, for something better, which animates us all and could animate psychology.

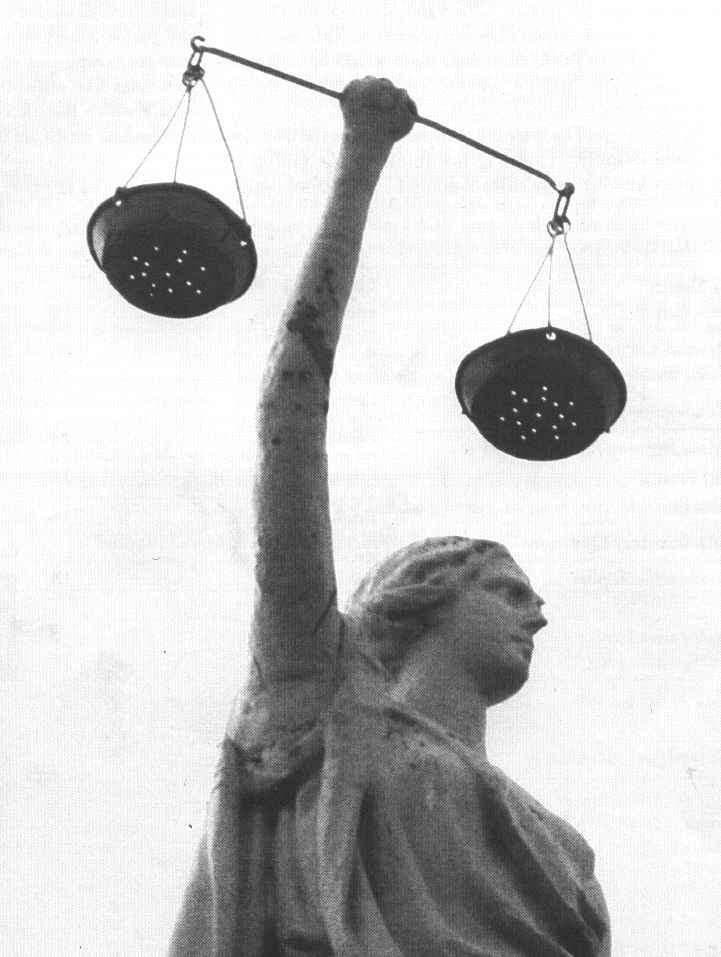

Our direction is broadly towards a just society, and our way is marked

by an explicit set of values. The values of justice, stewardship and community,

help define our priorities and our practices.

Justice:

If we are serious about justice as a value, we are serious about people's rights to self-determination; to a fair allocation of resources; to live in peace, with freedom from constraints; and to be treated fairly and equitably.

In pursuit of justice, we would be concerned with personal control or agency as well as with social influence, political power and legal rights. We might, for example, expose the ways in which authorities, established to be of service to people, wield their power and authority to effectively silence them; we might highlight inequities in how human services operate; we might work with people to secure access to the necessary supports, or work with services on a change agenda so that they work in a more inclusive and non-discriminatory way.

Stewardship:

If we are serious about stewardship as a value, we are serious about

our duties to look after our world and the people in it; to enable people

to make a contribution and gain a sense of social belonging; not to waste

things, people's lives, or time; and to think long-term, make things last

longer than us and to do things as right as we can.

In pursuit of stewardship, to make the best use of resources, we would work as efficiently as possible, maximising both human and material resources and work in ways that will lead to long lasting sustainable change and not just short term fixes. We would involve other people as fully as possible in innovation, sharing our expertise but not privileging it. Our emphasis would be on helping people change the context of their lives, through an emphasis on their creativity, strengths and potential. We would engage in a continual cycle of doing, learning and reflection.

Community:

If we are serious about community (as an abstract noun) as a value, we take seriously the different hopes and desires that people have, including the hope for companionship, love, acceptance and tolerance; the hope to be included, and for diversity to be welcomed and celebrated; and the hope that our individual and collective flaws will not hide our potential, and that we will all be accepted for who we are.

In pursuit of community, the focus of our work would be to strengthen

people's sense of social belonging , respect and commitment to each other,

irrespective of their history and social position. We would be in a position

to explore, expose and possibly bridge the rifts within communities, and

to understand ways in which strong communities can be excluding and intolerant

of diversity. We would stress conflict resolution via mediation and negotiation,

and would be concerned to be reflective and to evaluate our work constructively

and critically.

The Highway Code of Community Psychology

I have outlined the values, roles and skills of a community psychological practice. If we look back on the roads travelled so far, we can, finally, outline some principles for travelling the varied community psychological paths of the future.

An ecological and systems perspective

An ecological approach recognises the importance of the historical, environmental and situational context of people's lives, as well as the complexity of the social systems in which they live.

By taking an ecological approach, we are adopting a systems perspective in our work. Knowledge about how the social system operates, helps us understand the multiple causes of social problems, at different levels, from global to individual levels. Systems approaches also enable the different stakeholders in a particularly social problem, and/or its resolution to be identified and understood. This inevitably means we will be interested in analysing and using power in all its manifestations at different points in the social system. It is likely we will have to draw on other disciplines, such as management, environmental ecology, and social development for insights into this kind of work.

Prevention and social action

In community social psychological practice, we will often work with individuals and groups, not just on individual interventions for immediate problems, but rather in ways that divert resources towards problem prevention at any or all of the different levels of the social system. We might, for example, be working with individuals developing self-help strategies, or in terms of changing some aspect of the immediate environment that contributes to the problem. We might work alongside people caught up in and challenging an oppressive social institution. Alternatively, we might work at policy levels, be these local or national. It will not be enough to develop theoretical critiques of current practice and social problems: our work will need to have and support direct action that enhances both empowerment of groups or individuals, and wider scale social change, at the same time as finding ways to prevent the problem occurring. Working with the explicit value base outlined above, we will be in a position to lend both our expertise and our time to working alongside marginalised people contemplating or involved in direct social action for change. Our relationships with those with whom we work are likely to be long-term, and not limited to the time boundaries of a particular project.

Interdisciplinary work

As we have seen, it is important for us to recognise the artificial boundaries between different professional and academic disciplines. We will bring to our work a commitment to understand problems in different ways and to work collaboratively with others for better understanding and better use of resources at a local level. We will sometimes get involved in ways of helping those from different backgrounds come to a shared understanding of a problem and work together for effective solutions. Wherever possible we will develop strategies of working that maximise the joint resources different professionals or interest groups can bring to a problem. This emphasis on 'strategies' is important. It is not enough to work in interdisciplinary ways just because of contemporary exhortations that this is a good thing. We need to be purposive in our interdisciplinary work.

Collaboration, partnership and alliances

Closely linked to interdisciplinary working are collaboration and partnership. Relationships with community groups and organisations are viewed as partnerships, where each partner makes important contributions. It will not be up to us, the 'professional community psychologists' to identify for ourselves the important issues to be resolved. Instead, we will have to listen to local people about their concerns and viewpoints, and together negotiate a way of working towards shared goals. The work that community psychologists do will not be neutral. We will nurture a commitment to, and work with those who already share a commitment to a more just society and the values of justice, stewardship and community, whilst at the same time working to broaden this commitment.

Knowledge does not reside with the community psychology practitioner

or researcher: it is seen as jointly produced and owned by the workers

and local people, and joint decisions about publication and reporting of

the work will have to be made.

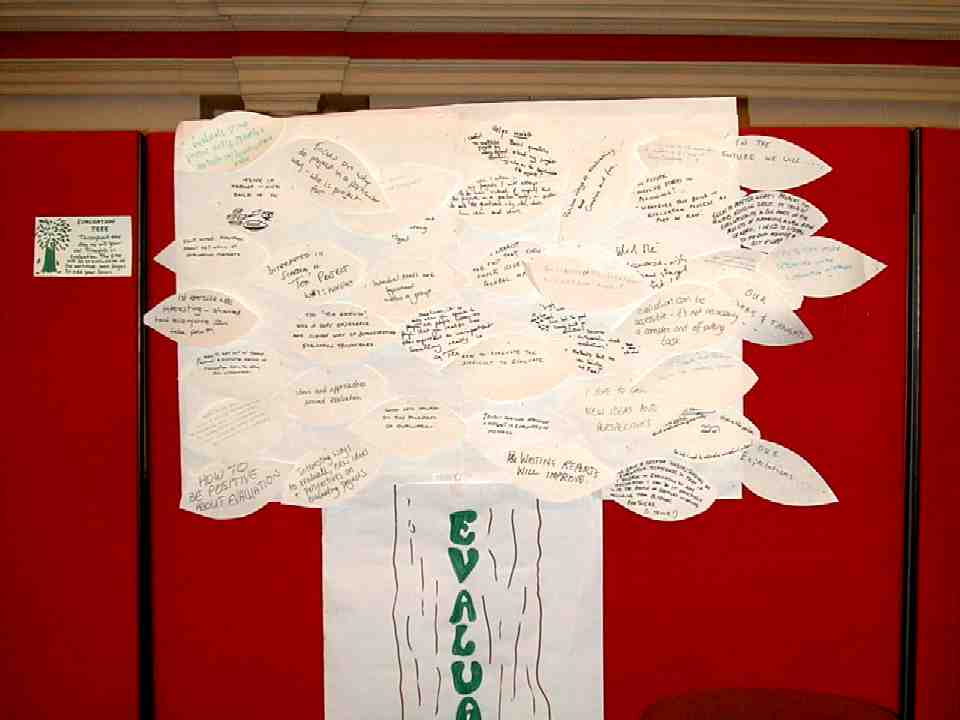

Critical reflection and evaluation

Throughout, as we can see, there will be an emphasis on change and learning from this change - both for ourselves and for others. We need to adopt a flexible approach, at the core of which is critical self-awareness, reflection and learning.

Evaluation is seen as an essential element of social change and social

innovation. It can identify positive and negative aspects of change and

contribute important information for both project improvement and for the

most efficient use of resources. Community social psychologists possess

skills in both statistical and non-statistical research, and are able to

undertake different kinds of evaluations themselves if required. Most importantly

though, we should be able to support local people in carrying out creative,

reflective evaluations that are robust and provide them, their projects

(and funders or commissioners) with both important information for the

future and celebration of achievements to date. Sometimes additional training

and support for local people in carrying out evaluations will be required,

and we may be well placed to carry out this kind of capacity building.

The

Liberation of Psychology

The

Liberation of Psychology

Developing such a community social psychology will, inevitably lead

to a change in emphasis in psychological training and in the discipline

of psychology itself. We have some way to go before we fully encompass

different social psychologies, such as those of Eastern Europe, post colonial

Africa, India and Latin America, and the understanding they bring with

them of how different historical, social and political contexts affect

people's lives.

We have to be prepared to push for and support a broad based education is psychology, including material from other disciplines.

We cannot separate our community psychological practice in the field from that of education. Thus our teaching and commitment to students should also enshrine the key values and principles of community psychological practice outlined above. Retaining a commitment to widening participation in higher education, non-traditional routes of entry for students and provision of supports required to enable them to succeed will be essential. Our approach must value diversity and go beyond a restrictive understanding of 'equality of opportunity' to 'equality of achievement'. We will need to be clear how our teaching and assessment practices serve sometimes to disempower rather than to empower students. In other words we need to develop a community social psychological approach to education, wherein students are active partners in all aspects of their learning - in practice not just in rhetoric.

Thus, I am suggesting, the future possibilities for community social psychology are for a liberated, liberating practice in which social action, theory and research are interconnected and create a critical praxis that is shared by all those working towards a just society.

If the possibilities for a community social psychology as outlined above are to be realised, we will need not just a liberation of psychological practice, but also a liberation of psychology.

I suggest that the creation and acceptance of a community social psychology may contirbute to just such a liberation. Who knows, perhaps community social psychology as a discipline will come to embody the philosophy of Ubuntu At this early stage, it seems to me that we do have the chance of treading carefully new, community social psychology paths, finding and making our way by walking with and through others. As I have suggested, a liberation of psychology is possible, but primarily, I suggest

psychology will only become a community psychology through others.

The end!